II. It’s an extraordinary amount of work to design precise and personalized assessments that illuminate pathways forward for individual students–likely too much for one teacher to do so consistently for every student. This requires rethinking of learning models, or encourages corner-cutting. (Or worse, teacher burnout.)

III. Literacy (reading and writing ability) can obscure content knowledge. Further, language development, lexical knowledge (VL), and listening ability are all related to mathematical and reading ability (Flanagan 2006). This can mean that it’s often easier to assess something other than an academic standard than it is knowledge of the standard itself. It may not tell you what you want it to, but it’s telling you something.

See also 12 Of Our Favorite Articles About Assessment

IV. Student self-assessment is tricky but a key matter of understanding. According to Ross & Rolheiser, “Students who are taught self-evaluation skills are more likely to persist on difficult tasks, be more confident about their ability, and take greater responsibility for their work.” (Ross & Rolheiser 2001)

V. Assessments of learning can sometimes obscure more than they reveal. If the assessment is precisely aligned to a given standard, and that standard isn’t properly understood by both the teacher and assessment designer, and there isn’t a common language between students, teacher, assessment designer, and curriculum developers about content and its implications, there is significant “noise” in data that can mislead those wishing to use the data, and disrupt any effort towards data-based instruction.

VI. Teachers often see understanding or achievement or career and college-readiness; students often see grades and performance (e.g., a lack or abundance of failure) (Atkinson 1964).

VII. Self-evaluation and self-grading are different. ‘Self-evaluation’ does not mean that the students determine the grades for their assignments and courses instead of the teacher. Here, self-evaluation refers to the understanding and application of explicit criteria to one’s own work and behavior for the purpose of judging if one has met specified goals (Andrade 2006).

VIII. If the assessment is not married to curriculum and learning models, it’s just another assignment. That is, if the data gleaned from the assessment isn’t used immediately to substantively revise planned instruction, it’s at best practice, and at worst, extra work for the teacher and student. If assessment, curriculum, and learning models don’t ‘talk’ to one another, there is slack in the chain.

See also Assessment Trends In Education: A Shift To Assessment For Learning

IX. As with rigor, ‘high’ is a relative term. High expectations–if personalized and attainable–can promote persistence in students (Brophy 2004). Overly simple assessments to boost ‘confidence’ are temporary. The psychology of assessment is as critical as the pedagogy and content implications.

X. Designing assessment that has diverse measures of success that ‘speak’ to the student is critical to meaningful assessment. Students are often motivated to avoid failure rather than achieve success (Atkinson 1964).

XI. In a perfect world, we’d ask not “How you do on the test,” but “How’d the test do on you?” That is, we’d ask how accurately the test illuminated exactly what we do and don’t understand rather than smile or frown at our ‘performance.’ Put another way, it can be argued that an equally important function of an assessment is to identify what a student does understand. If it doesn’t, the test failed, not the student.

XII. The classroom isn’t ‘the real world.’ It’s easy to say invoke ‘the real world’ when discussing grading and assessments (e.g., “If a law school student doesn’t study for the Bar and fail, they don’t get to become lawyers. The same applied to you in this classroom, as I am preparing you for the real world.”) Children (in part) practicing to become adults is different than the high-stakes game of actually being an adult. The classroom should be a place where students come to understand the ‘real world’ without feeling its sting.

When students fail at school, the lesson they learn may not be what we hope.

XIII. Most teachers worth their salt can already guess the range of student performance they can expect before they even give the assessment. Therefore, it makes sense to design curriculum and instruction to adjust to student performance on-the-fly without Herculean effort by the teacher. If you don’t have a plan for the assessment data before you give the assessment, you’re already behind.

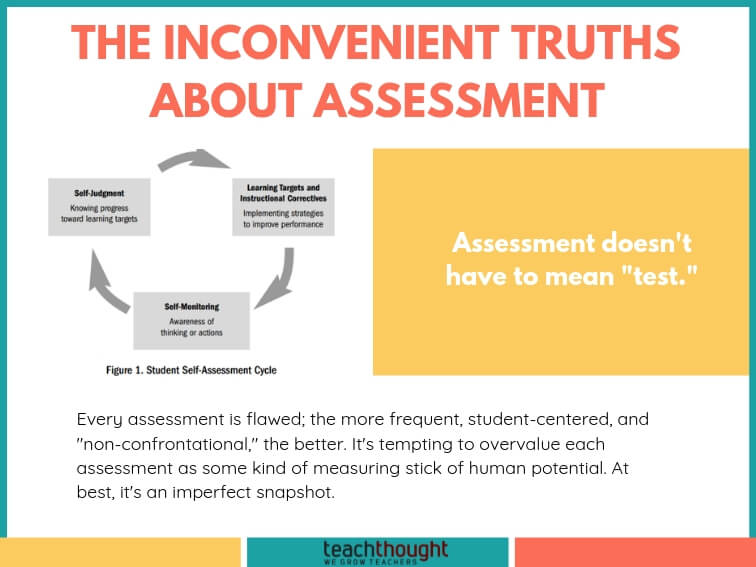

XIV. Every assessment is flawed. (Nothing is perfect.) That means that the more frequent, student-centered, and ‘non-threatening’ the assessment is (here are some examples of non-threatening assessments) the better. It’s tempting to overvalue each assessment as some kind of measuring stick of human potential. At best, it’s an imperfect snapshot–and that’s okay. We just need to make sure teachers and students and parents are all aware and respond to results accordingly.

XV. As a teacher, it’s tempting to take assessment results personal; it’s not. The less personal you take the assessment, the more analytical you’ll allow yourself to be.

XVI. Confirmation bias within assessment is easy to fall for–looking for data to support what you already suspect. Force yourself to see it the other way. Consider what the data says about what you’re teaching and how students are learning rather than looking too broadly (e.g., saying ‘they’ are ‘doing well’) or looking for data to support ideas you already have.

XVII. Assessment doesn’t have to mean ‘test.’ All student work has a world of ‘data’ to offer. How much you gain depends on what you’re looking for. (Admittedly, this truth isn’t really inconvenient at all.)

XVIII. Technology can help make data collection simpler and more effective but that’s not automatically true. In fact, if not used properly, technology can even make things worse by providing too much data about the wrong things (making it almost unusable to teachers).